Joseph G. McCoy and the Chisholm Trail, 1867-1871

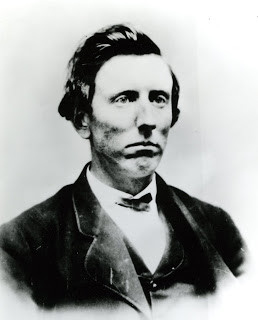

You cannot write anything about the history of Dickinson County, Kansas, without covering Joseph G. McCoy and his effect on cattle driving.

Joseph G. McCoy left a prosperous farm in Illinois and came to Kansas in 1867, where he planned to make his fortune in the cattle trade. He had heard reports of huge herds of cattle running wild in Texas after the Civil War. Their impoverished owners could not get the cattle to Northern Markets because the eastern trail had been closed by splenic fever, or “Texas Fever,” a disease brought north by ticks attached to longhorn cattle that killed thousands of domestic cattle. Farmers and ranchers north of Texas convinced state legislation to make quarantine lines that no longhorn was allowed to pass. McCoy devised a plan to drive the cattle to a railhead in Kansas outside the quarantine lines and then ship them back east, where the market for beef was higher because of a scarcity of the product.

McCoy wasted no time searching for a railhead on the new Union Pacific Railway line. He traveled to several communities, looking for an acceptable location to build a stockyard. He was turned down by many cities, including Junction City, Solomon City, and Salina. After being turned down by so many communities, McCoy focused his attention on the small community of Abilene. He had noticed Abilene during his journey to Salina and decided it would be a good place to build his stockyards. At the time, the town was rather small, mostly consisting of dugouts and sod houses. There was one major problem with using Abilene for his stockyards; the town was within the quarantine line. In mid-June 1867, McCoy negotiated an agreement with the local farmers and convinced Samuel Crawford, Governor of Kansas, to allow Texas cattle within the quarantine lines. Within a month, he had started the construction of loading pens in Abilene. McCoy sent men south to Texas to locate struggling herds and direct them to Abilene.

McCoy wasted no time searching for a railhead on the new Union Pacific Railway line. He traveled to several communities, looking for an acceptable location to build a stockyard. He was turned down by many cities, including Junction City, Solomon City, and Salina. After being turned down by so many communities, McCoy focused his attention on the small community of Abilene. He had noticed Abilene during his journey to Salina and decided it would be a good place to build his stockyards. At the time, the town was rather small, mostly consisting of dugouts and sod houses. There was one major problem with using Abilene for his stockyards; the town was within the quarantine line. In mid-June 1867, McCoy negotiated an agreement with the local farmers and convinced Samuel Crawford, Governor of Kansas, to allow Texas cattle within the quarantine lines. Within a month, he had started the construction of loading pens in Abilene. McCoy sent men south to Texas to locate struggling herds and direct them to Abilene.

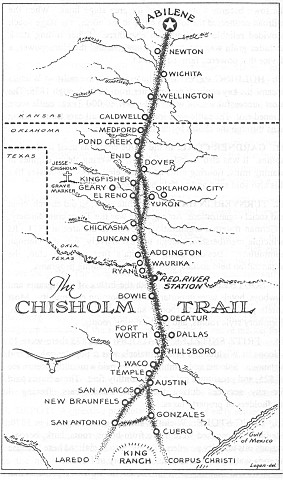

McCoy also sent Timothy Hersey, a land surveyor and pioneer of Abilene, to survey the Chisholm Trail and build mounds of dirt to mark the trail for drovers. At the time, they did not refer to the path as the Chisholm Trail, but in later years, it took that name. A portion of the trail had formerly been used by Jesse Chisholm as a trade route from the area near Wichita to a trading post near present-day Oklahoma City.

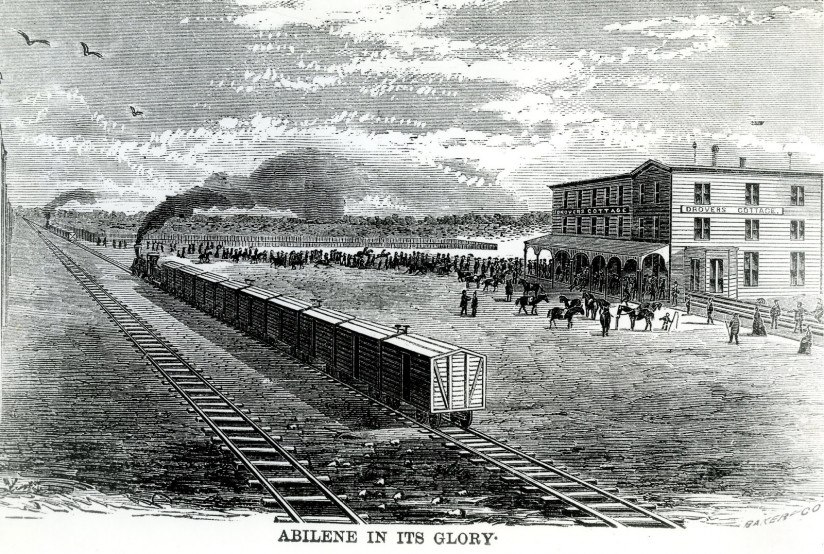

In addition to McCoy’s Great Western Stockyards, he also built a large hotel for cattle barons and drivers to stay when they arrived in Abilene. The hotel was known as the Drover’s Cottage and was known as one of the finest hotels in the West.

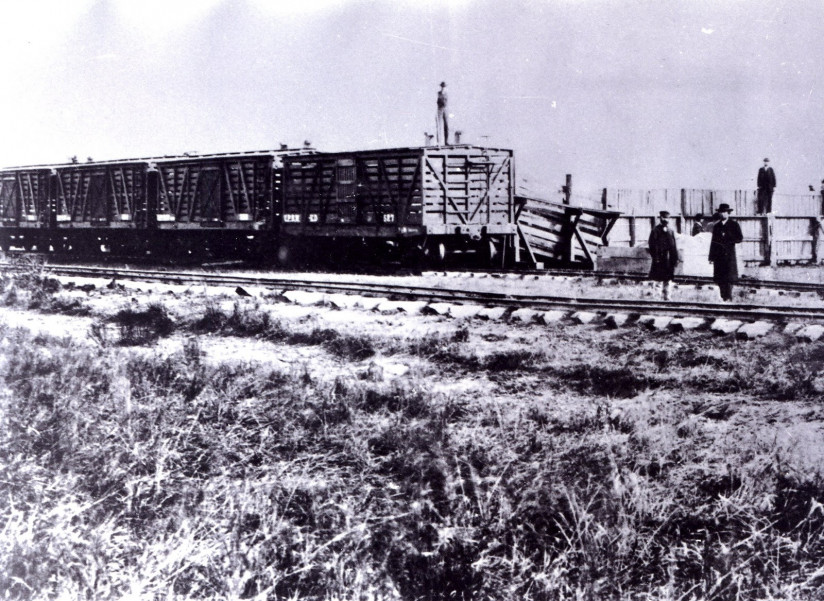

On August 15, before the pens were completed, 7,000 longhorns arrived in Abilene. Before the season was over, 35,000 head of cattle had arrived. The stockyards in Abilene were seen as a great success, and many stockyards began to appear in several Kansas towns. The six major cattle towns of the era were Abilene, Ellsworth, Newton, Wichita, Caldwell, and Dodge City. Many other Kansas towns shipped cattle as well, though. Below are approximate totals of the number of cattle driven up the Chisholm Trail from 1867 to 1871:

On August 15, before the pens were completed, 7,000 longhorns arrived in Abilene. Before the season was over, 35,000 head of cattle had arrived. The stockyards in Abilene were seen as a great success, and many stockyards began to appear in several Kansas towns. The six major cattle towns of the era were Abilene, Ellsworth, Newton, Wichita, Caldwell, and Dodge City. Many other Kansas towns shipped cattle as well, though. Below are approximate totals of the number of cattle driven up the Chisholm Trail from 1867 to 1871:

1867 35,000

1868 75,000

1869 150,000

1870 300,000

1871 600,000

When McCoy made his agreement with the Union Pacific Railway, the railway initially agreed to pay him five dollars for each car in which cattle were shipped. This was a verbal agreement; no physical contract was signed by either party. After the second season of the cattle trade in 1868, over $200,000 was due to McCoy. The railway refused to pay this amount on the claim that the agreement was “improvidently made.” McCoy surrendered on the agreement that a new contract would be made. This contract never came to fruition, and McCoy would not receive his payment until several years later after he sued the company for the amount due to him.

In 1868, Texas fever began making many of McCoy’s buyers from the east nervous about purchasing cattle from Abilene. McCoy had an incredible solution for this problem. The first part of his plan was to put on a show. He had a band of cowboys capture several native plains animals. After capturing several bison, elk, and wild horses, the cowboys traveled to St. Louis and Chicago, showing their prowess in riding and roping the various animals. This show impressed many of McCoy’s buyers. Soon after, McCoy invited his buyers to visit Abilene and go on a buffalo hunt. After the hunt, he brought the men to his stockyards and greatly praised the thousands of longhorns waiting to be sold. These cattle were bought soon, and McCoy’s business was booming again.

In addition to McCoy’s businesses opening in Abilene, several other businesses began to be seen throughout Abilene’s cattle town era. By 1870, the community had ten boarding houses, eleven saloons, five general stores, and four hotels. The community had grown to accommodate over seventy-five businesses and over three thousand residents. Most of these businesses found their income from cowboys and cattle traders. As many as one thousand cowboys were being paid off in a single day during the cattle drive season, and they spent their money quickly in the many businesses that Abilene had to offer.

A great example that shows what the economy was like in Abilene is the First National Bank. McCoy referred many cattlemen to the First National Bank of Kansas City for their banking needs. When the facility opened a local bank in 1870 in Abilene, over $900,000 passed over the counter in the bank’s first two months; this amount would be the equivalent of over $15 million today.

In 1872, due to an increase in domestic livestock deaths related to Texas Fever and an ever-growing problem with unlawful cowboys, Abilene passed an ordinance prohibiting Texas longhorns, making it necessary for ranchers to find new railheads to ship their cattle from. The following proclamation was issued: “We, the undersigned, most respectively request all who have contemplated driving cattle to Abilene to seek some other point for shipment, as the inhabitants of Dickinson County will no longer submit to the evils of the trade.” Joseph McCoy, who was Abilene's mayor then, did not agree with this decision.

McCoy was left bitter about what had happened in Abilene. He wrote of Abilene, “Four-fifths of her business houses became vacant, rents fell to a trifle, many of the leading hotels and business houses were either closed or taken down and moved to other points. The property became unsalable. The luxuriant sunflower sprang up thick and flourished in the main streets while the inhabitants, such as could not get away, passed their time sadly contemplating their ruin. Loud and deep, curses were freely bestowed on the political ring. The whole village assumed a lonely, forsaken and deserted appearance.”